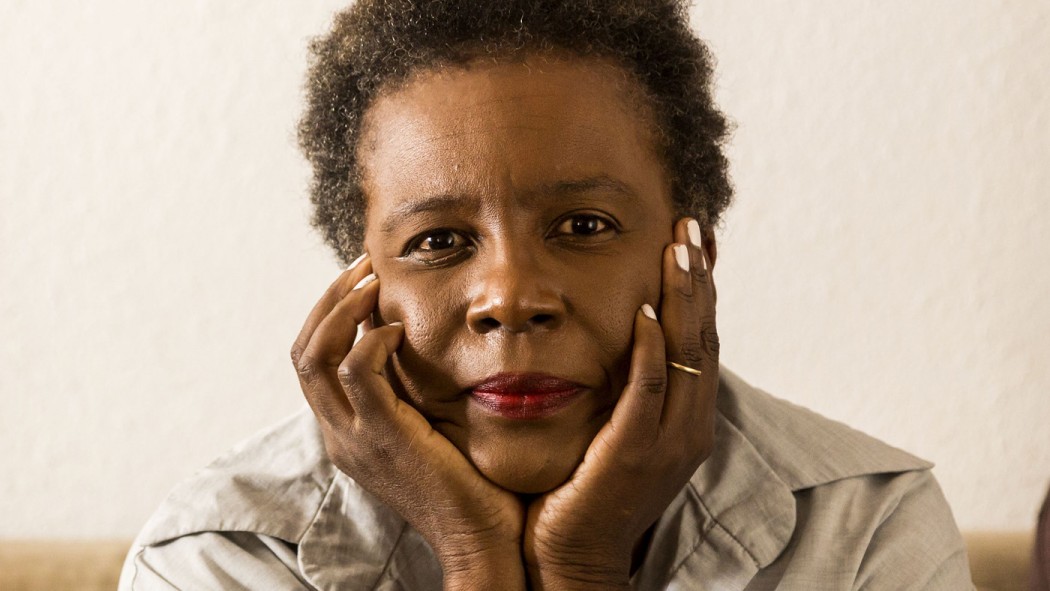

CLAREMONT, CA – SEPTEMBER 26, 2014 – Claudia Rankine en su casa (Ricardo DeAratanha/Los Angeles Times).

Claudia Rankine (Jamaica, 1963), se graduó en el Williams College y cursó un MFA (Máster en Creación Artística) en Columbia. Ha publicado varias colecciones de poesía, entre ellas Citizen (Ciudadanx), que fue finalista del National Book Award y obtuvo el National Book Critics Circle Award de poesía, el PEN Center Usa Poetry Award y el Forward poetry prize.

Es un libro fácil de encontrar, pero una lectura difícil (también de traducir), por lo que la cantidad de lectores que ha atraído encarna un síntoma. Al mezclar poesía, ensayo, autobiografía y arte conceptual hace una «puesta en escena» de la cuestión racial de una potencia que no se daba, tal vez, desde Ojos azules de Toni Morrison (aunque sea fácil pensar en salvedades a esa hipérbole, como Prelude to Bruise de Saeed Jones). Cada reedición aumenta la lista que aparece en sus últimas páginas, en la que recuerda a las víctimas afroamericanas de violencia policial.

29 Julio – 18 Agosto 2014 Haciendo sitio

Guión para una ficción pública en el Hammer Museum

En el tren la mujer que está de pie te hace pensar que no hay asientos libres. Y en realidad hay uno. ¿La mujer va a bajarse en la siguiente parada? No, preferiría estar de pie todo el trayecto hasta Union Station.

El espacio que hay junto al hombre es la pausa en una conversación que de pronto sientes la urgencia de llenar. Pasas rápido por encima del miedo de la mujer, un miedo que comparte con el resto. Dejas que se lo quede.

Conforme te sientas el hombre no se da por enterado porque el hombre sabe mucho más del sitio vacío que tú. Para él, imaginas, es como respirar, no le sorprende; se ha visto empujado a pensar tanto en ello que no lo llamarías pensamiento.

Cuando, al abandonar su asiento un pasajero, se sienta la mujer, le echas un vistazo al hombre. Hunde la mirada más allá de la ventana, en lo que parece oscuridad.

Te sientas al lado del hombre en el tren, autobús, el avión, sala de espera, en cualquier lugar en el que pueda estar maldito. Pones tu cuerpo ahí en su inmediación, adyacente, a lo largo, dentro.

No hablas de no ser interpelada y tu cuerpo le habla al espacio que llenas y te obcecas en llenarlo salvo que el espacio le pertenece al cuerpo del hombre que está junto a ti, no a ti.

Adonde él va, va el espacio. Si el hombre dejara su asiento antes de Union Station tú no serías más que una persona en un asiento del tren. Y dejarías de debatirte con el asiento sin ocupar cuándo dónde por qué el espacio no quiere perder su significado.

Imaginas que si el hombre hablara contigo diría: no pasa nada, estoy bien, no tienes que sentarte ahí. No tienes por qué sentarte y te sientas y miras más allá de él hacia la oscuridad que el tren se encuentra atravesando. Un túnel.

La oscuridad te permite, entretanto, mirar hacia él. ¿Nota que le miras? Lo sospechas. ¿Qué significado tiene la sospecha? ¿Qué hace la sospecha?

El gris verdoso suave de tu abrigo de algodón toca su manga. Estáis hombro con hombro aunque si fuerais de pie te sentirías empequeñecida. Te sientas en reparación de lo que ha hecho ¿quién a quién? Borras el pensamiento. Y demasiado tarde, a lo mejor.

Puede que sea siempre demasiado tarde o demasiado pronto. El tren se mueve demasiado rápido como para que tus ojos se acostumbren a nada que esté más allá del hombre, la ventana, el tunel embaldosado, su resbaladiza oscuridad. De vez en cuando pasa una luz blanca y centellea como un sonido fuera de lugar.

Más allá del pasillo vías habitáculo puerto mundo una mujer le pregunta a un hombre en las filas de adelante si le importaría que intercambiaran los sitios. Desea sentarse junto a su hija o su hijo. Oyes, pero no oyes. No puedes ver.

Es entonces cuando, el hombre que se sienta junto a ti, se gira hacia ti. Y, como asintiendo desde el interior de tu cabeza, convienes que si alguien te pide que te muevas le dirás viajamos en familia.

July 29–August 18, 2014 / Making Room

Script for Public Fiction at Hammer Museum

On the train the woman standing makes you understand there are no seats available. And, in fact, there is one. Is the woman getting off at the next stop? No, she would rather stand all the way to Union Station.

The space next to the man is the pause in a conversation you are suddenly rushing to fill. You step quickly over the woman’s fear, a fear she shares. You let her have it.

The man doesn’t acknowledge you as you sit down because the man knows more about the unoccupied seat than you do. For him, you imagine, it is more like breath than wonder; he has had to think about it so much you wouldn’t call it thought.

When another passenger leaves his seat and the standing woman sits, you glance over at the man. He is gazing out the window into what looks like darkness.

You sit next to the man on the train, bus, in the plane, waiting room, anywhere he could be forsaken. You put your body there in proximity to, adjacent to, alongside, within.

You don’t speak unless you are spoken to and your body speaks to the space you fill and you keep trying to fill it except the space belongs to the body of the man next to you, not to you.

Where he goes the space follows him. If the man left his seat before Union Station you would simply be a person in a seat on the train. You would cease to struggle against the unoccupied seat when where why the space won’t lose its meaning.

You imagine if the man spoke to you he would say, it’s okay, I’m okay, you don’t need to sit here. You don’t need to sit and you sit and look past him into the darkness the train is moving through. A tunnel.

All the while the darkness allows you to look at him. Does he feel you looking at him? You suspect so. What does suspicion mean? What does suspicion do?

The soft gray-green of your cotton coat touches the sleeve of him. You are shoulder to shoulder though standing you could feel shadowed. You sit to repair whom who? You erase that thought. And it might be too late for that.

It might forever be too late or too early. The train moves too fast for your eyes to adjust to anything beyond the man, the window, the tiled tunnel, its slick darkness. Occasionally, a white light flickers by like a displaced sound.

From across the aisle tracks room harbor world a woman asks a man in the rows ahead if he would mind switching seats. She wishes to sit with her daughter or son. You hear but you don’t hear. You can’t see.

It’s then the man next to you turns to you. And as if from inside your own head you agree that if anyone asks you to move, you’ll tell them we are traveling as a family.

*

[Extractos sin título intercalados entre los poemas-ensayo ]

Cuando la mujer con la que trabajas te llama por el nombre de otra mujer con la que trabajas, todo se convierte en un cliché demasiado grande como para no reírte con la amiga que está junto a ti que dice, no me lo puedo creer. Aun así, al final, ¿qué más da?, ¿a quién le importa?, tenía el cincuenta por ciento de opciones de acertar.

Sí, y en el email de disculpas que te envía se refiere a «nuestro error». Parece que tu propia invisibilidad es el verdadero problema, lo que le produce confusión. Así es como el dispositivo dentro del cual te empuja empieza a multiplicar sus significados.

¿Qué decías?

When a woman you work with calls you by the name of another woman you work with, it is too much of a cliché not to laugh out loud with the friend beside you who says, oh no she didn’t. Still, in the end, so what, who cares? She had a fifty-fifty chance of getting it right.

Yes, and in your mail the apology note appears referring to “our mistake.” Apparently your own invisibility is the real problem causing her confusion. This is how the apparatus she propels you into begins to multiply its meaning.

What did you say?

*

Al término de una breve conversación telefónica, le dices al encargado con el que has estado hablando que te pasarás por su oficina para firmar el formulario. Al llegar y presentarte, suelta de sopetón ¡no sabía que eras negra!

No quería decir eso, dice acto seguido.

En voz alta, dices.

¿Qué?, pregunta.

No querías decirlo en voz alta.

A partir de ahí la conversación va como la seda.

At the end of a brief phone conversation, you tell the manager you are speaking with that you will come by his office to sign the form. When you arrive and announce yourself, he blurts out, I didn’t know you were black!

I didn’t mean to say that, he then says.

Aloud, you say.

What? he asks.

You didn’t mean to say that aloud.

Your transaction goes swiftly after that.

*

Un amigo te cuenta que ha visto una foto tuya en internet y quiere saber por qué sales tan enfadada. Tú y el fotógrafo elegisteis la fotografía que menciona tras decidir ambos que era en la que salías más relajada. ¿Pareces enfadada? No se te hubiera ocurrido. Es evidente que esa imagen tuya sin sonrisa le hace sentir incómodo, y necesita que se lo justifiques.

Si aparecieras sonriendo, ¿qué despertaría en su imaginación, qué le diría tu manera de estar?

A friend tells you he has seen a photograph of you on the Internet and he wants to know why you look so angry. You and the photographer chose the photograph he refers to because you both decided it looked the most relaxed. Do you look angry? You wouldn’t have said so. Obviously this unsmiling image of you makes him uncomfortable, and he needs you to account for that.

If you were smiling, what would that tell him about your composure in his imagination?

*

Poco tiempo atrás te encuentras en una habitación en la que alguien le pregunta a la filósofa Judith Butler qué es lo que hace dañino al lenguaje. Notas cómo todo el mundo hace el gesto de acercarse. Es el mero hecho de existir lo que nos expone a ser interpeladas por el otro, contesta. Padecemos nuestro ser interpelables. Nuestra susceptibilidad de ser interpeladas lleva en sí nuestra apertura emocional, añade. El lenguaje se las ha con esto.

Pensabas, desde hacía tanto tiempo, que el propósito del lenguaje racista estaba en denigrarte y suprimirte como persona. Tras meditar las reflexiones de Butler, empiezas a comprender que tales actos de lenguaje lo que hacen es volverte hipervisible. El lenguaje que te hace sentirte dañada busca aprovechar todas las maneras que tienes de hacerte presente. Tu estado de alerta, tu apertura, tu deseo de involucrarte, en realidad requieren tu presencia, tu alzar la vista, tu decirle algo como contestación y, siendo una locura, decirle por favor.

Not long ago you are in a room where someone asks the philosopher Judith Butler what makes language hurtful. You can feel everyone lean in. Our very being exposes us to the address of another, she answers. We suffer from the condition of being addressable. Our emotional openness, she adds, is carried by our addressability. Language navigates this.

For so long you thought the ambition of racist language was to denigrate and erase you as a person. After considering Butler’s remarks, you begin to understand yourself as rendered hypervisible in the face of such language acts. Language that feels hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present. Your alertness, your openness, and your desire to engage actually demand your presence, your looking up, your talking back, and, as insane as it is, saying please.

*

Mientras haces cola en la farmacia, por fin llega tu turno, y de pronto no llega conforme él pasa de largo y pone sus cosas sobre el mostrador. El cajero dice, señor, era el turno de ella. Cuando se gira hacia ti se lleva una sorpresa genuina.

Ay dios, no te había visto.

Seguro que tenías prisa, le ayudas.

No, no, es que de verdad que no te he visto.

In line at the drugstore it’s finally your turn, and then it’s not as he walks in front of you and puts his things on the counter. The cashier says, Sir, she was next. When he turns to you he is truly surprised.

Oh my God, I didn’t see you.

You must be in a hurry, you offer.

No, no, no, I really didn’t see you.

*

Esperas a un amigo en el bar del restaurante en el que un hombre, por crear conversación, gestando algo, saca su móvil para enseñarte la foto de su mujer. La miras, como un puente que ha tendido, y dices que es hermosa. Lo es, dice, es una negra hermosa, como tú.

You wait at the bar of the restaurant for a friend, and a man, wanting to make conversation, nursing something, takes out his phone to show you a picture of his wife. You say, bridge that she is, that she is beautiful. She is, he says, beautiful and black, like you.

*

Cuando la camarera le da tu tarjeta de crédito a tu amiga, te ríes y le preguntas qué más va a conseguirle el privilegio de ser blanca. Oh, la vida perfecta que llevo, contesta. Y entonces las dos os ponéis a reír tan fuerte que todo el mundo en el restaurante acaba sonriendo.

When the waitress hands your friend the card she took from you, you laugh and ask what else her privilege gets her? Oh, my perfect life, she answers. Then you both are laughing so hard, everyone in the restaurant smiles.