Ilustración de Eleni Kalorkoti.

Si en algún momento de mi vida hubiese podido enterarme de qué futuro me deparaba, siempre hubiera querido saber si iba a tener o no hijos. Más que el amor, más que el trabajo, más que la duración de mi vida o de la cantidad de felicidad, esa era la pregunta cuyo misterio me resultaba más intrigante. Podía imaginarme el resto de esas cosas; parir no. Quería saber si iba a poder soportarlo, no porque esa información fuera a hacer mi maternidad imaginable, sino porque me parecía que el tema no podía permanecer en duda sin que se volviera una distracción. Era esta distracción, tanto como el tema de la maternidad misma, lo que quería tener bajo control. Consideraba a la maternidad una amenaza, una forma de discapacidad que te señalaba como a una distinta. Pero las mujeres debemos y tenemos que vivir con la perspectiva del parto: algunas le temen, otras lo desean y otras lo manejan tan exitosamente que hasta dan la impresión de que nunca piensan en eso. Mi propia estrategia era negarlo, así que llegué al asunto de la maternidad en shock y sin preparación, ignorante de cuáles serían las consecuencias de mi arribo a ella, y con la infundada pero distintiva impresión de que mi recorrido había sido tan aleatorio y tan determinado por fuerzas más poderosas que yo que difícilmente podría haberse dicho que yo había tenido algún tipo de decisión en el tema.

Este libro es un intento de describir algo de ese arribo, y del drama del cual el parto es solo la primera escena. Es, necesariamente, un recuento personal de un período de transición. Mi deseo de expresarme en el tema de la maternidad fue fuerte desde el principio, pero residía subterráneo, debajo de la superficie reconfigurada de mi vida. Unos meses después del nacimiento de mi hija Albertine, desapareció por completo. Deliberadamente me olvidé de todo lo que había sentido con tantas ganas hacía tan poco tiempo: no podía, de hecho, sentirlo. Mi apetito por el mundo era insaciable, omnívoro, una expresión de deseo de mi yo prematernal perdido, y de la libertad que ese yo quizás disfrutaba, quizás derrochaba. La maternidad, para mí, era una suerte de búnker alejado del mundo. Todo el tiempo planeaba mi escape, y cuando me vi embarazada de nuevo a los seis meses de Albertine, saludé a mi vieja celda con la deprimente aceptación de una presa que fue atrapada a lo grande. Lo que cautamente había pensado que era la libertad se convirtió en una hamaca tirante entre los troncos de mis dos embarazos: estaba rodeada, y fue ahí cuando la extraña realidad de la maternidad se volvió evidente para mí otra vez. Escribí este libro durante el embarazo y los primeros meses de mi segunda hija, Jessye, antes de que pudiera escaparme de nuevo.

Explico esto con la sombría sospecha de que un libro sobre maternidad no es de interés real para nadie más que para otras madres; e incluso solo para madres que, como yo, encuentran la experiencia tan trascendental que leer sobre ella tiene un raro efecto narcótico. Digo «otras madres»y «solo madres»como una disculpa: la experiencia de la maternidad pierde casi todo en su traducción al mundo exterior. En la maternidad una mujer intercambia su sentido público por una gama de significados privados y, como los sonidos que están fuera de cierto alcance, puede ser muy difícil que otras personas los identifiquen. Si una pudiera escuchar con una parte distinta de sí misma, quizás podría escucharlos.«Toda la vida humana de este planeta nace de una mujer», escribió Adrienne Rich. «La única experiencia unificadora e indiscutible compartida por todas las mujeres y varones es ese período de meses que pasamos desarrollándonos adentro del cuerpo de una mujer… La mayoría de nosotres conocemos primero el amor y la decepción, el poder y la ternura, a través de una mujer. Cargamos la impresión de esa experiencia de por vida, incluso en nuestra muerte».

Hay, por supuesto, muchos análisis, historias, polémicas y estudios sociales importantes sobre la maternidad. Fue examinado seriamente como un tema de clase, de geografía, de política, de raza y de psicología. En 1977, Adrienne Rich escribió el influyente Nacemos de mujer:maternidad como institución y experiencia, y fue inspirada en su ejemplo que ofrezco mi propio relato. Sin embargo, cuando me convertí en madre, mi impresión fue que no se había escrito absolutamente nada sobre el tema: este quizás sea un buen ejemplo de esa sordera que describí, con la que una persona que no es padre o madre es afectada cada vez que habla alguien que sí lo es, una condición que adquirimos en la infancia y que nos lleva más adelante a preguntarnos con confusión cómo es que nunca nos habían contado –nuestros amigues, ¡nuestras madres!–cómo era la pamaternidad. Estoy segura de que mi reacción, hace tres años, al libro que escribí ahora hubiera sido preguntarme por qué la autora se había molestado en primer lugar en ser madre si pensaba que era tan horrible.

Esta no es una historia o un estudio sobre maternidad; tampoco es, en el caso de que alguien haya leído hasta acá y tenga alguna esperanza, un libro sobre cómo ser una madre. Simplemente escribí lo que pensé sobre la experiencia de tener una hija de manera tal que otras personas pudieran identificarse. Como novelista, admito que este tipo de escritura sincerada me resulta un poco alarmante. Más allá de la perspectiva de una autorrevelación, demanda de parte del autor o autora una inclinación a violar la intimidad de aquellas personas que la rodean. En este caso, esa intrusión fue por omisión. No dije mucho sobre mis circunstancias particulares, ni las de las personas con las que vivo, ni sobre las otras relaciones que inevitablemente rodean la relación que tengo con mi hija. En su lugar, usé aspectos de mi vida como un lienzo sobre el que mi tema, que es la maternidad, podía ser ilustrado.

Pero el asunto de las hijas y de quién las cuida se volvió, desde mi punto de vista, profundamente político, por lo que sería una contradicción escribir un libro sobre la maternidad sin explicar mínimamente cómo encontré tiempo para escribirlo. Durante los primeros seis meses de vida de Albertine, la cuidé en casa mientras mi pareja seguía trabajando. Esta experiencia me mostró a la fuerza algo a lo que antes no le había prestado mucha atención: el hecho de que después de que un niño o una niña nace, las vidas de su madre y de su padre divergen, por lo que si antes vivían en algún estado de equidad, ahora viven en una suerte de relación feudal entre sí. Un día que se pasa en la casa cuidando une niñe no podría ser más distinto a uno trabajando en una oficina. Cualesquiera sean sus relativos méritos, son días que se pasan en lados opuestos del mundo. Desde ese comienzo difícil de reconciliar, vi como algo inevitable que nos sumergiéramos en un patriarcado más profundo: el padre pasaba sus días con la armadura del mundo exterior, del dinero, de la autoridad y la importancia mientras la madre cubría la esfera de lo doméstico. Es bien sabido que en parejas donde ambos trabajan full-time, la madre generalmente hace más que su justa cuota de tareas domésticas y de cuidado, y es la que acorta el día de trabajo para ocuparse de las exigencias de la pamaternidad. Ese es un asunto de política sexual; pero incluso en los hogares más generosos, en el cual reconozco que yo estoy, la brecha entre quien se ocupa del cuidado y quien trabaja es profunda. Cerrarla es extremadamente difícil. Una solución es que el padre se quede en casa mientras la madre trabaja: en nuestra cultura, lo masculino y lo femenino siguen tan divididos, tan encastrados en el conservadurismo, que un hombre tal vez podría cuidar a sus hijos sin sentir que es el sirviente de su pareja. Muy pocos hombres, sin embargo, se dispondrían a lastimar su carrera tomando ese rumbo; aquellos que estuvieran dispuestos a hacerlo estarían implícitamente más comprometidos con la igualdad que la mayoría, y arriesgarían la misma pérdida de autoestima que las mujeres que tienen a la maternidad como su única carrera. Ambos pueden trabajar y emplear a una niñera o niñero, o a veces cada cual puede acortar la semana y pasar algunos días en casa y otros en el trabajo. Esto suele ser más difícil si uno de los dos trabaja en casa, a pesar de la creencia común de que una carrera de este tipo es la «ideal»si tenés hijos. Una porción injusta de las responsabilidades domésticas para quien trabaja en casa resulta inevitable. Su rol termina pareciéndose al de esas personas que controlan el tráfico aéreo.

Yo creía, con el alegre y escaso sentimentalismo de quien no tiene hijos, que pagar un cuidado full-timeera la solución para el problema que había entre el trabajo y la maternidad. En esos días, la justicia me parecía todo. No entendía qué desafío al concepto de igualdad sexual iba a traer la experiencia del embarazo y el parto. El parto no es solamente lo que divide a las mujeres de los hombres: también los divide de sí mismos, dado que el entendimiento de lo que es existir para una mujer cambia de manera profunda. Otra persona existió en ella, y después del parto de ambos, viven en la jurisdicción de su propia consciencia. Cuando están con ella, ella no es ella; cuando no están con ella, ella no es ella; y por eso es que resulta tan difícil estar con tus hijas como no estarlo. Descubrir esto es sentir que tu vida se volvió irreparablemente enredada en conflicto, o envuelta en una trampa mítica en la que perpetua e inútilmente vas a luchar.

En mi caso, tomamos una decisión para demoler la cultura familiar tradicional de una vez, y fue vista por otras personas con sorpresa, aprobación y horror. La forma más punitiva e impracticable de ser de una familia parece menos merecedora de comentarios y preocupaciones generales que la simple originalidad. Mi pareja dejó su trabajo y nos mudamos de Londres. Las personas empezaron a preguntarnos por él como su estuviera muy enfermo, o muerto. ¿Qué va a hacer?, me preguntaban ávidamente, y después, sin conseguir mi respuesta, a él. Cuidar a las chicas mientras Rachel escribe su libro sobre cuidar a las chicas, era su respuesta. Esto a nadie le parecía particularmente gracioso.

Cuidar hijos es una ocupación de bajo estatus. Es solitario, frecuentemente aburrido, inexorablemente demandante y agotador. Erosiona tu autoestima y tu membresía al mundo adulto. Cuanto más separado estás del resto de la vida, más difícil se vuelve; y así y todo llevar a tus hijas a tu propio mundo, más que moverte al suyo, es duro también. Aun cuando acordás con una versión de la vida que es aceptable para todes, hay deseos que incluso no se satisfacen. Es mi creencia que en este proyecto la generosidad es más importante que la igualdad, aunque sea solo porque la demonología de la pamaternidad es tan católica que provoca epítetos de lo que es “bueno” o “malo” que están ausentes de nuestra experiencia ordinaria de vida. Como madre, aprendés lo que es ser al mismo tiempo la mártir y la diabla. En la maternidad me vi a mí misma más virtuosa y más terrible, y también más implicada en la virtud y el terror del mundo, que lo que habría creído posible desde la anonimidad de la existencia sin hijas.

En este libro traté de explorar algunos de estos temas con el objetivo de responder la gran pregunta de qué es pasar de ser una mujer a una madre. Mis definiciones, de mujer y de madre, continúan siendo vagas, pero el proceso sigue causándome una gran fascinación. Es, no tengo dudas, más o menos el mismo proceso que fue siempre, pero el recorrido es, según mi mirada, mucho más largo para nosotras que lo que lo fue para nuestras madres. El parto y la maternidad son los yunques sobre los que la desigualdad sexual se forjó, y las mujeres que en nuestra sociedad tienen responsabilidades, expectativas y experiencias similares a las de los hombres, tienen todo el derecho de acercarse a ella atemorizadas. Las mujeres cambiaron, pero su condición biológica se mantiene igual. Como tal, la maternidad provee una ventana única a la historia de nuestro sexo, pero su vidrio se rompe fácilmente. A mí me sigue maravillando el hecho de que cada miembro de nuestra especie nació y consiguió su independencia en tan arduo camino. Es este trabajo, requisado de la vida de una mujer, el que traté de describir.

Este libro es un modesto acercamiento al tema de la maternidad, escrito al calor de su temática. Describe un período que parece rondar en círculos mucho más que en orden cronológico, y por eso traté de capturarlo en temas más que en la olvidada progresión de sus días. Sin dudas va a haber otros años con verdades humanas que habría deseado esperar para registrar. En su lugar, tomé prestadas esas verdades de otres, incluyendo en este libro algunas novelas que leí o recordé mientras escribía, y que me pareció que tenían algo para decir sobre mi temática. Es una selección parcial y personal: la literatura descubrió y documentó hace mucho tiempo este espacio del que pensé que era la primera habitante, y hay incontables poemas y novelas que podrían reemplazar a aquellas que elegí. Mencioné los libros más para ilustrar la particular transformación de la sensibilidad que produce la maternidad que para encontrar su expresión perfecta: mi experiencia con la lectura, en realidad con la cultura, cambió profundamente por el hecho de tener una hija, en el sentido de que descubrí que el concepto de arte y expresión eran mucho más comprometedores y necesarios, mucho más humanos en su impulso por hacer nacer y crear, que lo que antes creía.

Por el momento, se trata de una carta, dirigida a aquellas mujeres que tengan ganas de leerla, con la esperanza de que encuentren algo de compañía en mi experiencia.

Traducción de Bárbara Duhau

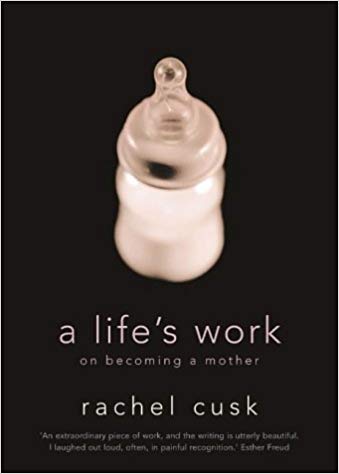

Portada de A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother de Rachel Cusk.

If at any point in my life I had been able to find out what the future held, I would always have wanted to know whether or not I would have children. More than love, more than work, more than length of life or quantity of happiness, this was the question whose mystery I found most compelling. I could imagine those other things; giving birth to a child I could not. I wanted to know whether I would go through it, not because this knowledge would have made motherhood imaginable, but because it seemed to me that the issue could not remain shrouded in uncertainty without becoming a distraction. It was this distraction, as much as the fact of motherhood itself, that I wanted to have within my control. I regarded it as a threat, a form of disability that marked me out as unequal. But women must and do live with the prospect of childbirth: some dread it, some long for it, and some manage it so successfully as to give other people the impression that they never even think about it. My own strategy was to deny it, and so I arrived at the fact of motherhood shocked and unprepared, ignorant of what the consequences of this arrival would be, and with the unfounded but distinct impression that my journey there had been at once so random and so determined by forces greater than myself that I could hardly be said to have had any choice in the matter at all.

This book is an attempt to describe something of that arrival, and of the drama of which childbirth is merely the opening scene. It is, necessarily, a personal record of a period of transition. My desire to express myself on the subject of motherhood was from the beginning strong, but it dwelt underground, beneath the reconfigured surface of my life. A few months after the birth of my daughter Albertine, it vanished entirely. I wilfully forgot everything that I had felt so keenly, so little time ago: I couldn’t bear, in fact, to feel it. My appetite for the world was insatiable, omnivorous, an expression of longing for some lost, pre-maternal self, and for the freedom that self had perhaps enjoyed, perhaps squandered. Motherhood, for me, was a sort of compound fenced off from the rest of the world. I was forever plotting my escape from it, and when I found myself pregnant again when Albertine was six months old I greeted my old cell with the cheerless acceptance of a convict intercepted at large. What I had begun cautiously to think of as freedom became an exiguous hammock slung between the trunks of two pregnancies: I was surrounded, and it was then that the strange reality of motherhood grew apparent to me once more. I wrote this book during the pregnancy and early months of my second daughter, Jessye, before it could get away again.

I make this explanation with the gloomy suspicion that a book about motherhood is of no real interest to anyone except other mothers; and even then only mothers who, like me, find the experience so momentous that reading about it has a strangely narcotic effect. I say ‘other mothers’ and ‘only mothers’ as if in apology: the experience of motherhood loses nearly everything in its translation to the outside world. In motherhood a woman exchanges her public significance for a range of private meanings, and like sounds outside a certain range they can be very difficult for other people to identify. If one listened with a different part of oneself, one would perhaps hear them. ‘All human life on the planet is born of woman,’ wrote the American poet and feminist Adrienne Rich. ‘The one unifying, incontrovertible experience shared by all women and men is that months-long period we spent unfolding inside a woman’s body … Most of us first know both love and disappointment, power and tenderness, in the person of a woman. We carry the imprint of this experience for life, even into our dying.’

There are, of course, many important analyses, histories, polemics and social studies of motherhood. It has been seriously examined as an issue of class, of geography, of politics, of race, of psychology. In 1977 Adrienne Rich wrote the seminal Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Institution and Experience, and it is inspired by her example that I offer my own account. Yet it was my impression, when I became a mother, that nothing had been written about it at all: this may merely be a good example of that tone-deafness I describe, with which a non-parent is afflicted whenever a parent speaks, a condition we acquire as children and which leads us as adults to wonder in bemusement why we were never told –by our friends, by our mothers! –what parenthood was like. I am certain that my own reaction, three years ago, to the book I have now written would have been to wonder why the author had bothered to have children in the first place if she thought it was so awful.

This is not a history or study of motherhood; nor, in case anyone has read this far and still retains such a hope, is it a book about how to be a mother. I have merely written down what I thought of the experience of having a child in a way that I hope other people can identify with. As a novelist, I admit that I find this candid type of writing slightly alarming. Aside from the prospect of self-revelation, it demands on the part of the author a willingness to trespass on the lives of those around him or her. In this case, I have trespassed by omission. I have not said much about my particular circumstances, nor about the people with whom I live, nor about the other relationships inevitably surrounding the relationship I describe with my child. Instead I have used aspects of my life as a canvas upon which my theme, which is motherhood, may conveniently be illustrated.

But the issue of children and who looks after them has become, in my view, profoundly political, and so it would be a contradiction to write a book about motherhood without explaining to some degree how I found the time to write it. For the first six months of Albertine’s life I looked after her at home while my partner continued to work. This experience forcefully revealed to me something to which I had never given much thought: the fact that after a child is born the lives of its mother and father diverge, so that where before they were living in a state of some equality, now they exist in a sort of feudal relation to each other. A day spent at home caring for a child could not be more different from a day spent working in an office. Whatever their relative merits, they are days spent on opposite sides of the world. From that irreconcilable beginning, it seemed to me that some kind of slide into deeper patriarchy was inevitable: that the father’s day would gradually gather to it the armour of the outside world, of money and authority and importance, while the mother’s remit would extend to cover the entire domestic sphere. It is well known that in couples where both parents work full-time, the mother generally does far more than her fair share of housework and childcare, and is the one to curtail her working day in order to meet the exigencies of parenthood. That is an issue of sexual politics; but even in the most generous household, which I acknowledge my own to be, the gulf between childcarer and worker is profound. Bridging it is extremely difficult. It is one solution for the father to remain at home while the mother works: in our culture, the male and the female remain so divided, so embedded in conservatism, that a man could perhaps look after children without feeling that he was his partner’s servant. Few men, however, would countenance the injury to their career that such a course would invite; those who would are by implication more committed than most to equality, and risk the same loss of self-esteem that makes a career in motherhood such a difficult prospect for women. Both parents can work and employ a nanny or childminder, or sometimes each can work a shorter week and spend some days at home and some at work. This is rather more difficult if one of you works at home, in spite of the widely held belief that a career such as my own is ‘ideal’ if you have children. An unfair apportioning of domestic responsibility to the home worker is unavoidable. Their role begins to resemble that of an air traffic controller.

Full-time paid childcare was what I, with the blithe unsentimentality of the childless, once believed to be the solution to the conundrum of work and motherhood. In those days fairness seemed to me to be everything. I did not understand what a challenge to the concept of sexual equality the experience of pregnancy and childbirth is. Birth is not merely that which divides women from men: it also divides women from themselves, so that a woman’s understanding of what it is to exist is profoundly changed. Another person has existed in her, and after their birth they live within the jurisdiction of her consciousness. When she is with them she is not herself; when she is without them she is not herself; and so it is as difficult to leave your children as it is to stay with them. To discover this is to feel that your life has become irretrievably mired in conflict, or caught in some mythic snare in which you will perpetually, vainly struggle.

In my case a decision was made to demolish traditional family culture altogether, and it was regarded by other people with amazement, approval and horror. The most punitive, unworkable version of family life appears to be less worthy of general comment and concern than simple unconventionality. My partner left his job and we moved out of London. People began to enquire about him as if he were very ill, or dead. What’s he going to do? they would ask me avidly, and then, getting no answer, him. Look after the children while Rachel writes her book about looking after the children, was his reply. Nobody else seemed to find this particularly funny.

Looking after children is a low-status occupation. It is isolating, frequently boring, relentlessly demanding and exhausting. It erodes your self-esteem and your membership of the adult world. The more it is separated from the rest of life, the harder it gets; and yet to bring your children to your own existence, rather than move yourself to theirs, is hard too. Even when you agree on a version of living that is acceptable to everybody, there are still longings that go unmet. It is my belief that in this enterprise generosity is more important even than equality, if only because the demonology of parenthood is so catholic, drawing to itself epithets of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ that are largely absent from our experience of ordinary life. As a mother you learn what it is to be both martyr and devil. In motherhood I have experienced myself as both more virtuous and more terrible, and more implicated too in the world’s virtue and terror, than I would from the anonymity of childlessness have thought possible.

I have tried to explore some of these issues in this book, with the aim of answering the larger question of what it is to turn from a woman into a mother. My definitions, of woman and of mother, remain vague, but the process continues to exert on me a real fascination. It is, I don’t doubt, much the same process that it has always been, but the journey involved is, in my view, far longer for us than it was for our own mothers. Childbirth and motherhood are the anvil upon which sexual inequality was forged, and the women in our society whose responsibilities, expectations and experience are like those of men are right to approach it with trepidation. Women have changed, but their biological condition remains unaltered. As such motherhood provides a unique window to the history of our sex, but its glass is easily broken. I continue to marvel at the fact that every single member of our species has been born and brought to independence by so arduous a route. It is this work, requisitioned from a woman’s life, that I have attempted to describe.

This book is a modest approach to the theme of motherhood, written in the first heat of its subject. It describes a period in which time seemed to go round in circles rather than in any chronological order, and so which I have tried to capture in themes rather than by the forgotten procession of its days. There will doubtless be other years for whose insights I will wish I had waited. Instead I have borrowed the insights of others by including in this book some discussion of those novels that I read or recalled during its writing, which seemed to me to give voice to my theme. It is a partial and personal selection: literature has long since discovered and documented this place of which I thought myself to be the first inhabitant, and there are countless poems and novels that could take the place of those I have chosen. It is more to illustrate the particular transformation of sensibility that motherhood effects than to find its most perfect expression that I have mentioned books at all: my experience of reading, indeed of culture, was profoundly changed by having a child, in the sense that I found the concept of art and expression far more involving and necessary, far more human in its drive to bring forth and create, than I once did.

For now, this is a letter, addressed to those women who care to read it, in the hope that they find some companionship in my experiences.

Rachel Cusk nació en Canadá en 1967, pero desde 1974 vive en Inglaterra. Es autora de nueve novelas y tres libros de memorias. Entre su obra destacan las novelas La salvación de Agnes (1993, ganadora del Premio Whitbread a la primera novela), The Country Life (1997, ganadora del premio Somerset Maugham), Arlington Park (2006) y A contraluz (2014, finalista de los premios Folio, Goldsmiths, Baileys, Giller Prize y del Canadian Governor General’s Award,) y los libros autobiográficos A Life’s Work (2001) sobre la maternidad y Aftermath: On Marriage and Separation (2012). A contraluz (2014; Libros del Asteroide 2016) es la primera de una serie de tres novelas con la misma protagonista que la han consolidado como una de las escritoras más brillantes de la literatura inglesa actual. La segunda es Tránsito (2016; Libros del Asteroide, 2017) y la tercera, Prestigio (2018).

Bárbara Duhau (Buenos Aires, 1989). Licenciada en Comunicación (UBA), Diplomada en Comunicación, Género y Derechos Humanos (CPI-OEA), especialista en innovación creativa y escritora. Tiene más de diez años de experiencia en creación y producción de contenidos para medios tradicionales y digitales. De 2014 a 2017 co-dirigió la organización Un Pastiche – Género y Comunicación, cuya misión fue ampliar y mejorar las imágenes y la participación de las mujeres en los medios de comunicación y la industria cultural. Publicó los libros Criaturas insensibles (Galmort, 2009) y Forasteras (La Parte Maldita, 2013). Actualmente dirige el estudio de estrategia y creatividad Supernova y la comunidad digital de escritura, feminismo y maternidad Vida Propia.